The instruments onboard Chandrayaan-3’s lander have provided the first-ever direct measurements of high plasma density near the Moon’s (/Lunar) surface, close to the south pole. This finding strongly supports the long-debated existence of a lunar ionosphere, a mystery that has puzzled scientists for nearly 70 years. The discovery further validates a dense plasma layer of lunar origin, varying with the Sun’s position, and opens up a new chapter in our understanding of lunar physics and plasma dynamics.

Introduction

Let us begin by feeling the atmospheric conditions around the Moon. On Earth, atmospheric pressure at the surface is about 1 bar, but on the Moon it is a mere 10⁻¹⁵ bar, essentially negligible. Similarly, the number density of neutral particles on the Moon is about 1020 times lower than that of Earth. To put it simply, the density in Earth’s atmosphere at an altitude of 300 km is roughly equivalent to that at the lunar surface.

Close to the Moon’s surface, the neutral number density is around 10⁵ particles per cubic centimeter (cc). Despite these extreme conditions, the moon shows evidence of an ionospheric layer with high plasma density attached to its surface. The ionosphere is an atmospheric layer where electrons and ions exist freely alongside neutral particles and have enough density to influence radio signals. Since radio signals are widely used in communication, the presence of the ionosphere is of great interest to scientists.

A Brief History of Observations

The lunar ionosphere was first hinted at in the late 1950s, when scientists observed angular shifts in radio signals from distant natural sources as they passed near the Moon. These shifts could be explained by the refraction of radio waves in a lunar ionosphere with electron densities of about 1000 cm⁻³ and a thickness of a few tens of kilometers. Such experiments are known as stellar occultations.

Later, in 1966, the Pioneer 7 probe used radio signals from an onboard oscillator to directly probe plasma near the Moon, again reporting densities of the same order. This was an early radio occultation experiment.

Here’s how observations advanced across missions:

- Luna 19/20 (USSR): Detected plasma density peaks (~1000 cm⁻³) at altitudes of 10–40 km, mainly in the dayside polar terminator regions.

- Kaguya (Japan): This was a unique mission by Japan to measure plasma variations around the moon. They used two spacecraft in different orbits to simultaneously probe the ionosphere with two stable coherent radio signals; these observations are expected to be more accurate, which can easily filter out noise from other sources. Based on several observations, they detected an average plasma density of about 300 per cc on the sunlit side of the Moon.

- Chandrayaan-1 (India): Utilized ground-generated radio signals to probe near the lunar south pole in the evening, finding values consistent with Kaguya.

- Chandrayaan-2 (India): Carried a dual-frequency radio occultation experiment. Surprisingly, it detected higher plasma densities on the nightside, contradicting the long-standing belief that the lunar nightside lacked an ionosphere.

From these results, the global scientific community largely agreed that the Moon possesses an ionosphere extending up to ~40 km, with peak densities between 300–1000 cm⁻³.

But wait, if so much data already exists, where is the controversy?

The Conflict in Theory

Here’s the twist. Many researchers argue that such plasma densities should not be possible, based on fundamental physics. Let’s break this down.

- Ionization vs. Solar Wind Removal:

- Extreme Ultraviolet (EUV) radiation from the Sun ionizes neutral particles, creating plasma. With a neutral density of ~10⁵ cm⁻³, one might expect even higher plasma densities than observed.

- However, the solar wind, a constant stream of energetic particles, sweeps ions away. Theoretical models predict that only about 1 cm⁻³ plasma should remain, nearly 1000 times less than observed.

- Earth’s Ionosphere Contamination:

- Some argue that the observed signals are artifacts from Earth’s ionosphere. Since radio occultation involves signals passing through both Earth’s and the Moon’s plasma environments, disentangling the two effects is extremely challenging.

So, how do we reconcile this?

Alternative Explanations

Several theories have been proposed to explain the puzzling results:

- Photoelectrons: Electrons emitted from the lunar surface under solar radiation could accumulate and form an ionospheric layer, though this alone seems insufficient.

- Magnetic Trapping: Localized magnetic fields near the surface could trap plasma and shield it from the solar wind. Chandrayaan-2 provided supporting evidence for this.

- Mini-Magnetospheres: Remnant magnetic fields have been found on the lunar surface by the Apollo and Lunar Prospector missions, and the observed field intensities reach ∼300 nT on spatial scales up to 1000 km. It was suggested that such local magnetic fields can stand off the solar wind to create mini-magnetosphere systems near the surface. This result was further validated by the Japanese Nozomi spacecraft.

- Dusty Plasma Hypothesis: Charged dust grains near the lunar surface could be accelerated upward by the near-surface electric field and reach high altitudes. Charged dust clouds might be accompanied by substantial numbers of electrons. However, the recent measurements could not observe the proposed dust particles and thus neglected this theory.

The Puzzle of Apollo Measurements

The Apollo landers attempted in-situ plasma measurements but reported values 100 times lower than radio science results. This discrepancy puzzled scientists for decades, until later studies pointed out major uncertainties and limitations in those early instruments.

Chandrayaan-3’s Breakthrough

For the first time, Chandrayaan-3 provided direct, reliable in-situ measurements of the lunar ionosphere.

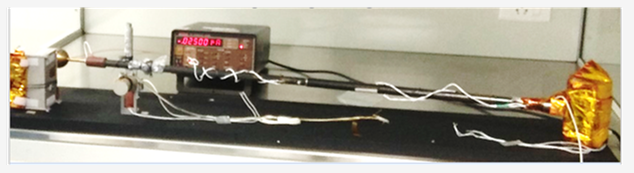

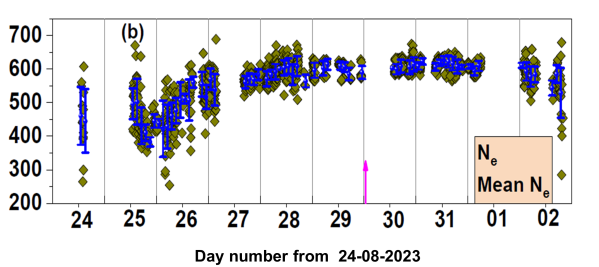

Using a Langmuir Probe (LP), essentially a small copper sphere mounted about one meter above the surface, based on the potential difference it measured, currents from the surrounding plasma were determined. From the measured current, electron densities of 400–600 cm⁻³ were derived, in excellent agreement with past remote-sensing studies.

This landmark result confirms the lunar ionosphere’s existence and challenges theorists to refine models of plasma dynamics on an airless body.

Attempt at Explanation

Researchers at the Space Physics Laboratory, VSSC, ISRO, who developed the Langmuir Probe, have modeled these observations. They suggest that lunar plasma is primarily produced by photoionization, dominated by molecular ions. While based on simplifying assumptions, the model reproduces the observed densities and provides a starting point for further exploration.

Summary

The Chandrayaan-3 lander has made a historic discovery: direct confirmation of a dense lunar ionosphere. These results align with decades of remote-sensing evidence but now stand on much firmer ground thanks to in-situ measurements.

The “battle of the lunar ionosphere,” fought for over half a century, has reached a turning point. Yet, the challenge remains for scientists worldwide to fully explain how the Moon sustains such plasma in the face of harsh solar wind conditions.

Reference:

[1] G. Manju, T. K. Pant, N. Mridula, Md. M. Hossain, K. M. Ambili, P. P. Kumar, T. V. Sruthi, V. K. S, R. S. Thampi, A. N. Aneesh, K. R. Tripathi, P. Sreelatha, R. John, In-situ ionospheric observations near lunar south pole by the Langmuir Probe on Chandrayaan-3 Lander, MNRAS (2025). https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/staf1276

Discover more from New Wave Particle

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Very well written. The language is simple. Appreciate such articles down the road. Ciao!!